„The reality for queer people is very different from what’s written on paper”

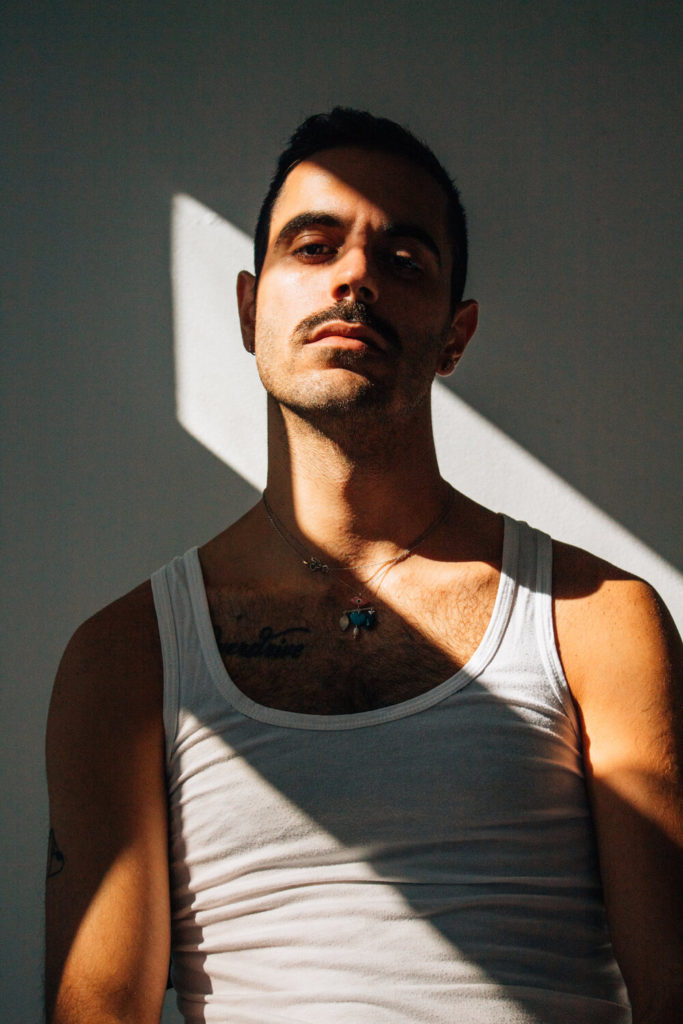

Interview with Bulgarian director and choreographer Kosta Karakashyan

His short film titled They, which tells the story of the hidden love between two male university professors, took years to complete. However, just as it was finished, the Bulgarian version of the homophobic law was introduced. But Karakasyhan (IG: @kostakarakashyan) is not discouraged; on the contrary, he is ready for the fight, just as he has always been. An activist, he plans and creates a series of queer films, including a short film with choreography about the struggles of the LGBTQ+ community in Chechnya. We talked with Kosta about the unique connection between creation and queer rebellion, the familiar exclusionary steps of Bulgarian homophobic politics, and the constant changes in society. We also learned why Bulgaria might be in a better position than Hungary. A deep interview.

Bár csak most fejezted be a They című rövidfilmedet, láttam Instagramon, hogy már a következőn dolgozol. A megállíthatatlan alkotó vagy?

They kind of opened up my appetite for telling more stories. I was already working on one upcoming feature film called Corruption. It’s about a closeted pop star in the 80s in Soviet Bulgaria. A dramatic, but also really funny story about everything he had to hide to make it and become the country’s most famous singer. The story is inspired by a lot of people who are famous today—people we have some clues about, but none of them are publicly out. It got me thinking about how they managed their careers.

When we wrote the first draft of the script with my co-writer, we realized it’s a really ambitious and expensive movie to make. We want to recreate all these big song contests from the former Soviet countries—like Yugoslavia, Croatia, and so on. So, it’s a tricky project for a debut film.

That’s when I started working on July Morning, another film, which is more manageable from a production standpoint. It’s a bit more intimate and cheaper to make. It’s about a young guy in his twenties who’s maybe realizing for the first time that he’s bisexual. He’s caught between this sexy Scandinavian guy who’s visiting for the summer and his ex-girlfriend, and he has to figure out how to navigate everyone’s feelings. It’s a coming-of-age story about those first experiences as you’re growing up.

With filmmaking, I feel like you can create something really three-dimensional that people can connect with and believe in.

It’s accessible. I started out as a choreographer, and sometimes with dance, it’s hard to get that same closeness with the audience. But with film, anyone can watch it and enjoy it, and get something out of it.

As I understand it, your new films also explore queer stories. Why is it so important for you to create queer art?

With my stage work, I sometimes explore other topics that interest me, but with film, one of the first pieces of advice you get as a screenwriter is to „write what you know.” I have so many vivid moments in my life that I think would translate really well to film. Even when I’m just walking down the street and hear something funny or interesting, or if I find myself in a tough situation, part of me is already thinking, “This could make a great scene for a project.”

As for queer stories, I feel like now is a crucial time to share them, especially in Bulgaria. Queer stories can be deeply emotional and also universal, which I think a lot of people don’t realize. The recent law banning LGBTQ „propaganda” in schools in Bulgaria is a good example of this disconnect.

I believe one reason the law passed so easily—despite being based on fake news—is because Bulgarian society still doesn’t fully understand why these stories are so vital.

If you look at the history of the US, for example, with the Civil Rights Movement and later the fight for LGBTQ rights, entertainment has often been one of the first ways marginalized groups carve out space for themselves. So, with my queer stories, I hope to create something entertaining and moving, something that builds empathy in people. Many of them only know queer people through the propaganda they hear, but they’ve never heard the real stories.

It’s true that queer art can make a real impact on society. But that also puts queer art in a special position—it’s not just art, it can also become a weapon. A lot of filmmakers, writers, and singers involved in queer art don’t really like that. They don’t like the idea that their art has to serve as a tool for democracy or social change. How do you feel about that?

There’s definitely some tension there because, as an artist, you always want to express yourself freely. Sometimes you just want to create something for the sake of creativity, maybe even a utopia, without always having to reflect on society. But for me, growing up, my whole family were doctors, and I really thought I would follow that path. That was until I turned 18 and got invited to join Dancing with the Stars in Vietnam as a professional dancer. I like to say that’s when show business seduced me. After being on the show, I realized that my art could be my voice.

But over time, I noticed the projects I wanted to make kept coming back to social topics. I think if you’re someone who has an interest in helping people—whether you’re a doctor or not—it eventually shows up in your art. For me, that shift happened with my first short film, WAITING FOR COLOR. It was an experimental mix of dance and documentary about the persecution of queer people in Chechnya. It was based on real stories of people who had been kidnapped and tortured. I used those stories to create choreography—the dance draws you in, but as you’re watching, you hear the brutal reality of what happened to these people.

It was a powerful way to combine my work as a dancer with the issues I care about. When something really touches me, I think about it constantly, and if I don’t create something from that, I feel restless. So personally, I don’t feel restricted or pressured to work on these topics. But I do understand the desire for more artistic freedom.

Ideally, I’d love to see a world where queer artists don’t always have to lead with their identity in their work.

That’s something really special about queer art—it’s in this unique position. Of course, you want to entertain, inspire, and show a different side of the world, but there’s also this responsibility to teach people something. So what’s your purpose as a creator? What makes you feel like you’ve accomplished what you set out to do?

For me, it’s about creating a bridge between an experience that most people might never have and the experience of someone who knows it deeply. It doesn’t always have to be me as the writer, but with They, the first version of the script actually came from a close friend of mine. He gave it to me as a gift, to see if I could imagine something coming out of it. What really moves me is when you can feel that there’s a whole life behind a work—whether it’s a writer, an actor, or whoever—there’s something substantial there.

So my purpose is to be that bridge, to connect the real story or whatever inspired it with the audience. I want to be the channel that allows every person watching to feel even a little bit of what’s behind the story.

I’ve read that you spent three years working on They. What was that journey like? How did it feel to spend such a long time on one project?

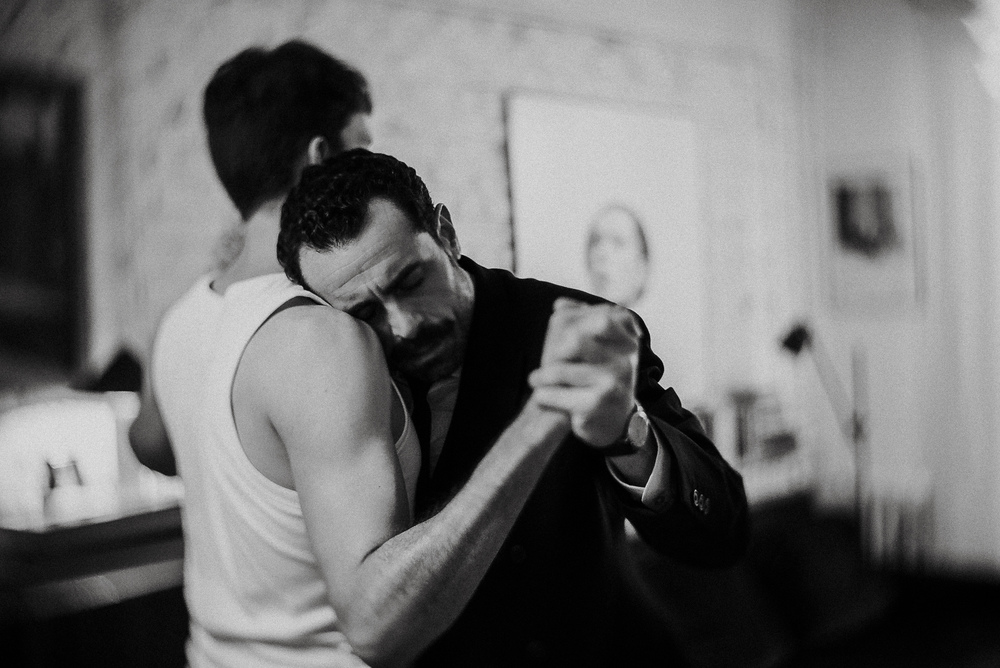

It was definitely a long process. Like I mentioned, I first read the script in 2020, and it’s evolved a lot since then. The story is about keeping a relationship private and how that secrecy affects it. It’s about two professors who hide their relationship at work, but we see that they’re a couple in private.

Getting funding for the film was interesting because internationally, we received a lot of great feedback. Everyone agreed that a movie like this was needed in Bulgaria. But when we pitched it here at a festival pitching session, I’ll never forget the reaction. Some film professionals told us there was no real social issue in Bulgaria—they said something like, “If you’re a professor, you could be dating a man, a woman, or even an animal, and nobody would care.” They were completely unaware of the stigma that still exists, even in countries without homophobic laws.

The reality for queer people is very different from what’s written on paper. With film, you can tap into what’s below the surface. You can show the emotional landscape of the characters through their actions—or even their inactions. It’s an amazing way to get inside a character’s head. We also had a lot of fun creating the side characters. Some are quiet allies, while others represent the difficulties of coming out. One iconic character, an older professor, is super traditional and always dominates the space in any situation at the university. It was fun translating all those feelings into a visual language.

In the movie, you show the love between these two men at the university. Is the problem with their relationship specific to universities in Bulgaria, or is it generally difficult for gay men or women to be open about their relationships in society?

It’s still difficult. We don’t have any publicly well-known queer couples in Bulgaria. There’s Lucy Diakovska, a lesbian singer, but she splits her time between Germany and Bulgaria, so I think that’s a bit different. Aside from her, there aren’t any positive queer examples in the media. Unfortunately, it can still be dangerous for queer couples to walk down the street, holding hands or kissing. Violent incidents still happen, not that often, but even in Sofia, the capital, it occurs. It’s worse in smaller towns.

So yes, it’s still a problem, and with the recent law, we’re seeing a psychological kind of fear—people have this big misunderstanding about what queerness is. They worry it’s something their children could „learn” as a behavior.

We weren’t necessarily making a statement about queer people in academia. But now, with the new law, it’s become very relevant.

In Hungary, we don’t really see aggression from society, but the government is definitely trying to make society more homophobic. The people, though, aren’t naturally like that—they’re resisting those efforts. Is it similar in Bulgaria? Is the state trying to push people to be homophobic or transphobic?

Absolutely. The way they rallied so quickly around this law was in response to an LGBTQ organization that was conducting an online survey in schools. This project was fully compliant with Bulgarian law, but it was twisted into a narrative about „drag queens going into schools and trying to convert kids.” It’s the same rhetoric we see elsewhere. It plays on people’s emotions, and they react quickly without checking the facts. They don’t open five websites to verify the source; they respond in a very primal, fearful way.

But if we’re going to look at it in a positive light, this is where art can be powerful. Art taps into emotions, and that’s always faster and more effective than trying to appeal to someone’s rational mind.

How has this new law affected your plans? You started this movie three years ago, and of course, the law wasn’t in place back then—it was only introduced this fall, so it’s pretty recent. I’m not sure how it’s being enforced in Bulgaria, but in Hungary, it’s almost impossible to show an LGBTQ-related movie in theaters. How have you reacted, and what changes have you made? How do you plan to show this movie to audiences?

For us, the new law mainly deals with propaganda in schools, so it doesn’t directly affect theatrical distribution. But I think we’ll actually use it as a platform for discussions and debates. I’m sure there will be some controversy when the movie comes out next year—just the fact that the main characters are university professors might stir things up. But I think it’s important to use this film as a mirror for society.

We’re definitely planning screenings in Bulgaria, but our first goal is to get international backing by premiering at festivals. If the film gains attention internationally, it will have a much bigger impact in Bulgaria. Here, if something gets recognized abroad or receives a lot of attention, the national media and communities become more interested in why it’s getting that response.

So while it’s a slower, less direct route, we’re hoping for a strong international showing before bringing it back home. By early next year, we should have a clearer idea of the landscape and, hopefully, some good news from the festivals.

I love how positive you are about this. It’s hard for me to respond, though, because two years ago in Hungary, we also thought the law was just about protecting children or dealing with issues in schools. But now, two or three years later, we’re seeing the bigger, negative consequences of the propaganda law. While it’s officially focused on children, there are far fewer queer movies and books being made. There’s a kind of self-censorship happening—film distributors, publishers, and even the artists themselves are holding back. Some artists in Hungary decide not to take the risk because they’re unsure if what they create will be seen as propaganda, so they don’t even try. Do you worry that this could happen in Bulgaria, that it could stifle queer culture or create some kind of suppression?

Maybe. But the queer scene in Bulgaria is still quite young. There are only a handful of artists who were making this kind of work even before the law. I see it as a mission—something that needs to exist. I’m lucky to be able to balance my work. Like any artist, I want a lot of people to see my work, so I also do commercials and music videos to support myself. That way, when I make these queer projects, I can do them without compromise and stay true to the vision I have. I know the audience for it is there—it’s just a matter of being brave, staying safe, and putting it out there.

I hope we can learn from the examples of Poland and Hungary. One small advantage we have is that this is happening later in Bulgaria, so we can see where things might head.

Sometimes, these terrible situations can actually have some positive effects. In Hungary, I’ve noticed that younger generations used to be quite passive or indifferent about LGBTQ rights and the political scene. But ever since these new homophobic laws were introduced, people in the community have become more angry, more active. They’re learning about the laws, organizing protests, and thinking more about their role in art and activism. Do you think these negative forces can actually give queer people more strength, as we’ve seen throughout history?

It’s an endless battle. If we have the strength to be part of it, we should do our part.

You’ve been an activist for many years and involved in queer art as a dancer and choreographer. Have you ever felt afraid?

I’m pretty stubborn and persistent when it comes to my views. The time I spent in New York was really formative. When I made my first film about Chechnya, I was living in New York, walking around Hell’s Kitchen, where there are so many gay bars, and you can just flirt with anyone on the street. At the same time, I was reading about the horrors happening in Chechnya. I realized how lucky I was to be born in Bulgaria, where things aren’t as bad, but then I saw what life could really be like in New York. I promised myself that if I ever moved back to Bulgaria, I wouldn’t let the environment limit my freedom.

I’m also lucky to have found my partner, Alexander, who feels the same way. That was a big concern for me when I moved back—whether I’d find someone here who was as comfortable in their own skin as I am. He’s been a huge source of courage for me, and over time, I’ve realized that there are more brave people here than I initially thought.

I think one of the most important things we can do within our own circles is to show that we’re not afraid. That can be really transformative.

Do you work together?

Yes! He used to be a pastry chef, but he’s also incredibly artistic. He’s been part of some of my dance performances, and we even created an immersive theater show together based on his stories from the kitchen. He’s dancing in it alongside dancers from my company Karakashyan & Artists. We love working together. He’s always the first person to watch rough cuts of my films, and he gives me great feedback. When I’m juggling a thousand projects and stressing out, he’s the one who brings balance and calm into my life.

Have you ever experienced a situation like the one between the two professors in your movie?

Not with Alex, but when I first moved back to Bulgaria, I had a boyfriend, and that relationship really informed so much of the film. I remember a situation where he was worried about a cleaning lady who would come to his apartment occasionally. He was scared she would figure out that I’d been there. Coming back from New York, that fear felt so foreign to me, but it was a big deal for him. The idea that someone who cleans your apartment once or twice a month might know something about your life that you didn’t want them to know—that it could change things or be used against you—that fear was very real for him.

The emotions behind that fear really shaped the movie. When I worked with the actors, I tried to convey how queer people often feel like they’re playing chess, thinking five steps ahead just to protect themselves.

Are there any festivals where the film will be shown, or can you share any details about its premiere? Will there be an online premiere in the future?

We’re in the waiting stage right now, just starting to submit to festivals. I’m hoping we’ll have some good news by January or February. We’re planning screenings in both the States and Europe. We’ll also be releasing the trailer soon on the film’s social media channels—They short film on Instagram (IG: @theyshortfilm) and Facebook (FB: They / Te). We’re revealing things bit by bit, so there will be a lot of exciting updates before people get to see it. I really hope the audience in Hungary will get a chance to see it soon too!

Ádám András Kanicsár (IG: @kanicsar)

Screens for They